Why wasn’t the Ming Dynasty very focused on the Western Regions?

Generally, China’s ancient unified dynasties sought to conquer the Western Regions. The Han Dynasty sent numerous missions there to fight the Xiongnu, and by the Eastern Han, they directly administered it. The Tang Dynasty’s efforts go without saying. Why does it seem that the Ming Dynasty wasn’t very focused on the Western Regions?

Viewpoint 1:

Actually, it’s the opposite; the Ming Dynasty was overly focused on the Western Regions.

The primary role of the Western Regions for the Huaxia Empire in ancient times was to provide a third party for trade between the steppe and the Han heartland, creating a tripartite trade structure.

Bilateral trade alone easily falls into extreme zero-sum games. With tripartite trade, win-win mutual benefit is much more achievable.

By the Qing Dynasty, due to advances in production technology, the development of waterways in North Asia, and Northwestern Europe finally escaping poverty via Africa + Atlantic trade (which in turn boosted Russian agriculture with American crops), the scale of this tripartite trade finally surpassed that of the Inner Asian Silk Road trade during the Han and Tang eras.

But during the Yuan and Ming periods, the situation was completely different.

The Yuan and Ming periods were the era when Inner Asian Silk Road trade was most desolate.

Productivity had advanced compared to the Han and Tang eras, yet the decline in Inner Asian trade volume far outpaced any boost from this development.

Conservative estimates in papers assessing Tang Dynasty Silk Road trade volume put the annual total at nearly 4 million Tang bolts of silk; optimistic estimates reach 8 million. This is roughly equivalent to the value of 400,000 medium-quality Uighur warhorses (High: 40 bolts/silk per horse, Medium: 30, Low: 20).

For most of the Yuan and Ming periods, the annual trade volume coming from Central Asia was only about 3,000-4,000 medium-quality Uighur warhorses.

That is to say, despite increased productivity, due to worsening natural conditions and the decline of Inner Asian civilizations, trade during the Yuan and Ming actually plummeted to 1% of Tang levels.

This trade volume was even smaller than the trade between the Han heartland and the notoriously poor and harsh Tibetan region.

Under these circumstances, the Ming Dynasty’s energy invested in the northwestern frontier actually exceeded the point of positive returns.

Many might not know that the early and mid-Ming also spent considerable sums supporting a large number of Mongol nobles from Xinjiang and even farther away, or Mongol-Semu mixed nobles, living idly off government support in Beijing.

The Eastern Chagatai Khanate + some noble families would have the eldest son stay in Xinjiang, while the second and third sons came to Beijing to secure official posts, bringing not just themselves but entire families and personal guards.

In the ninth year of the Zhengtong reign (1444), if I recall correctly, Emperor Yingzong specifically ordered that minor Mongol nobles from the Oirat + and other regions seeking refuge would no longer be settled near Beijing but relocated to the Nanjing area instead. This was because the area from Tianjin to Beijing and Baoding was already crowded with such people.

After the Tumu Crisis+, many of these Tatar officials and nobles indeed rebelled.

Of course, some remained loyal and served the court; it wasn’t all rebellion, and one shouldn’t generalize crudely.

Actually, the early Ming capital Beijing also had many foreigners, but it didn’t feel as prominent as in the Tang. The main reason is that Chang’an+ was the paramount routine commercial hub, but Beijing wasn’t…

Or rather, it wasn’t a routine trade hub.

Beijing was the core hub for trade between the Han heartland and the steppe, and for tributary trade with foreign states. But this trade came with heavy political and strategic baggage; it wasn’t natural.

There was a significant natural trade flow stretching from Yangzhou and other areas in East China all the way to West Asia.

Although the Tang government strictly controlled its own merchants and private trade ventures abroad, it welcomed Central and West Asian merchant caravans to come and trade in Chang’an.

Large-scale caravans from Central/West Asia coming to the Ming was impossible – they’d lose money for sure.

The Mongols were willing to trade on a large scale at horse markets, but could you afford not to control them?

Wouldn’t you restrict their numbers?

If not for the repeated rise and destruction by forces like Tibet and the Later Turkic Khaganate+, the Tang’s trade structure was quite healthy. The Ming’s was somewhat pathological.

One more point to mention: the Ming Dynasty’s investment in and focus on the southwest was also unprecedented among dynasties, yet you rarely see anyone ask why XX dynasty didn’t value the southwest.

In the Sinocentric historical view prevalent among certain domestic factions today, Inner Asia still retains a sense of superiority, as if we settled peoples within the passes are inferior to the horse peoples of North and Inner Asia.

Viewpoint 2:

The Mongol Western Campaigns, marching along the Silk Road, massacred everyone, destroyed all irrigation facilities, and annihilated all city-state civilizations, effectively destroying the Silk Road+.

The Ming army looked west beyond the Hetao region at the vast desert and was utterly bewildered – this didn’t match the historical records at all.

So they toiled, planting trees bit by bit, advancing slowly.

Viewpoint 3:

It wasn’t a lack of focus, but limitations imposed by conditions!

Feng Sheng and Fu Youde’s Western Expeditionary Army captured the Hexi Corridor+ but then withdrew because of supply difficulties.

What did this difficulty entail?

During Emperor Wu of Han’s reign (Han Dynasty), the eight commanderies of Liangzhou+ in the Hexi Corridor had a combined population of 1.03 million. Even the smallest, Dunhuang Commandery, had over 30,000 people.

During the Tang Zhenguan era, Longyou Circuit+, governing the Hexi Corridor, had a population of over 190,000. By the Kaiyuan era, it grew to over 550,000.

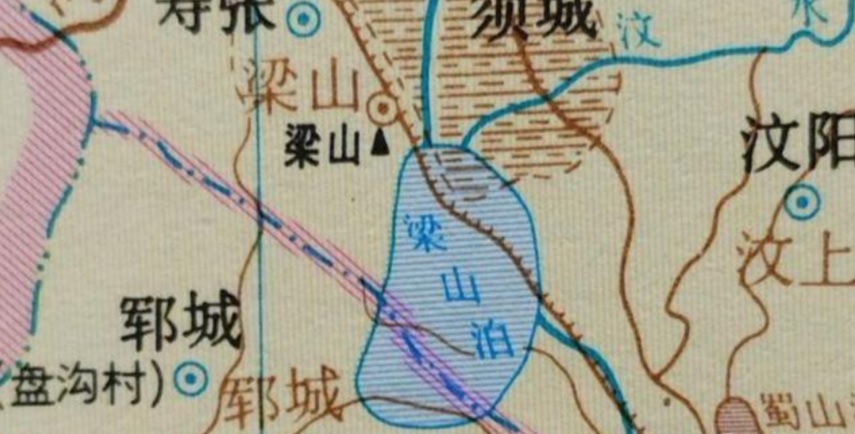

In contrast, when the Ming army marched west, they found only 30,000 people in the entire Hexi Corridor. Ganzhou (Zhangye) had only 830 households left – fewer than the expeditionary army itself. The Han population ratio was extremely low; Fu Youde practically needed translators the whole way. Such conditions made sustaining army logistics impossible.

Therefore, under these circumstances, the historical task of the early Ming wasn’t to “restore Han-Tang glory” or “reclaim the Protectorate of the Western Regions” for map-painting expansion, but to quickly restore the Han population in the north and northwest, reducing the demographic and economic disparities between north and south.

Simply occupying the Western Regions couldn’t be achieved by military force alone; it required sufficient population and economic foundation to support a stable military presence in the northwest.

Furthermore, changes in the northwest’s geography were a major factor.

During the Han and Tang periods, the Western Regions were dotted with oases and water sources. The natural conditions and habitability were far superior to the Ming era, sufficient to support local kingdoms and residents.

By the Yuan and Ming periods, desertification in the Western Regions had severely intensified, arable land drastically reduced, and many former kingdoms had vanished due to environmental deterioration and wars. It could no longer support large populations like in Han-Tang times.

Soil erosion in Gansu and the Loess Plateau also worsened significantly. Like the Western Regions, desertification accelerated, reducing the land’s carrying capacity.

The facts prove that even after large-scale migrations to the Hexi Corridor during the Hongwu and Yongle reigns, its population never returned to historical peaks.

Actually, both Zhu Yuanzhang (Hongwu Emperor) and Zhu Di (Yongle Emperor) had ambitions for the Western Regions. But if even the nearby Hexi Corridor couldn’t be populated enough, forcing reliance on loose control through nominal titles and enfeoffment to stabilize the situation (the Seven Garrisons West of Jiayu Pass+ were mainly composed of ethnic minorities from the western frontier)…

Even though the early Ming state and military could muster a large army to campaign west, conquer Yilibali+ (Ming name for the Eastern Chagatai Khanate after its 1418 capital move from Beshbalik), or even Herat (in the Timurid Empire), was feasible…

Being able to attack didn’t mean effective occupation was possible. Without favorable geography, sufficient logistics, and local population support, withdrawal was inevitable.

By the mid-to-late Ming, although northwest population conditions had improved somewhat, the court no longer had sufficient national strength or military power to advance and consolidate rule over the Western Regions.

However, by the Ming period, the strategic value of the Western Regions had greatly diminished. The primary reason was the environmental changes mentioned above. Environmental degradation drastically reduced the population-carrying capacity, meaning the support and security it could provide to imperial armies, merchants, and envoys paled in comparison to earlier times.

On the other hand, maritime transport gradually surpassed land transport in importance.

During the Song and Yuan periods, maritime trade between China and Southeast Asia/Indian Ocean coastal states was already flourishing, becoming a major source of revenue for the Southern Song.

In the early Ming, navigation and shipbuilding technology advanced further. Through Zheng He’s voyages+, the court established official institutions like Pacification Commissions in Palembang (Sumatra), India, Ceylon (Sri Lanka), the Arabian Peninsula, and East Africa, building ports, transit stations, official factories, and tax offices, ensuring smooth maritime links with the “Southern and Western Oceans” (Nanyang & Xiyang).

After the mid-Ming, the opening of new sea routes brought Western colonists to the Far East. Maritime trade between the Ming and European states grew closer, with silver flowing into China.

Compared to land transport, maritime shipping’s enormous capacity and cost advantages became undeniable. The Maritime Silk Road+ naturally attained equal importance to the overland Silk Road, making the economic value of Ming engagement with the Southern Seas as significant as engagement with the Western Regions.

Viewpoint 4:

The Ming Empire’s primary external threats were not in the Western Regions. In its founding period, the main focus was on dealing with the Northern Yuan and its splinter factions, the Oirats and Tatars. In the mid-late period, the threat shifted to the Later Jin rising in Liaodong, alongside frequent harassment by Japanese pirates (Wokou) along the coast.

From the late Yuan to early Ming, Mongols occupied the Western Regions, severely damaging irrigation systems. Many farmlands went unirrigated, leading to salinization and desertification due to extreme weather. War compounded by natural disaster caused the Western Regions’ population to plummet from hundreds of thousands in Han-Tang times to only around 30,000 in the early Ming – insufficient to support garrisons or administrative structures. The region was controlled by the Eastern Chagatai Khanate (Yilibali) and the Timurid Empire, who were only superficially friendly towards the Ming while harboring their own agendas. Constant ethnic strife (Mongols, Uighurs, Muslims) meant the Ming couldn’t cultivate a reliable proxy. The Seven Garrisons West of Jiayu Pass were essentially seven Mongol tribes west of Jiayu Pass, where the Yuan had established the Beiting Regional Military Commission. After Northern Yuan forces withdrew, these tribes only nominally accepted Ming titles; they were actually controlled by the Eastern Chagatai Khanate. Due to supply difficulties, the Ming couldn’t station troops long-term, leaving them effectively beyond reach.

The Yongle Emperor (Zhu Di) also promoted Zheng He’s voyages, official trade, and diplomacy. The court began exploring the new world via the Maritime Silk Road. A new door had opened, significantly reducing the importance of the Western Regions.

The Yongle Emperor’s expansionist policies strained finances. Subsequent emperors Renzong and Xuanzong had to implement contraction policies, abandoning the Nurgan Regional Military Commission, Annam (Vietnam), etc. Emperor Yingzong (Zhu Qizhen), acting obstinately, suffered the catastrophic defeat at Tumu Fort, where the Ming elite army was almost annihilated, leaving them even less capable of contesting the Western Regions. Later, as the Timurid Empire declined, the Islamic Ottoman Empire rose further west, controlling key land routes between the Balkans/Turkey and the East. Thereafter, trade via the Silk Road became very dangerous for Christian Europeans.

Europeans began dispatching numerous explorers, culminating in the late 15th century with sea routes bypassing the Ottomans to reach China’s southeast coast – the Age of Exploration began. East-West trade entered a new era, the overland Silk Road declined, and trade volume plummeted. During the reign of Emperor Xiaozong (Hongzhi, Zhu Youcheng), Columbus discovered the New World. Simultaneously, Vasco da Gama reached India via Africa, opening the sea route from Europe to India, permanently establishing the sea passage between Europe and the East. European fleets were already frequenting South and Southeast Asia; the Maritime Silk Road was unimpeded. In summary, by the mid-Ming, with the rise of new maritime trade routes, expanding into the Western Regions lost its meaning, and the court had no intention of investing more energy there.

Epilogue: By the late Ming, with the rise of the Later Jin in Liaodong, the empire’s main focus shifted there. To suppress them, the court spent heavily to form the Guanning Army, building the famous Guanning-Jinzhou defense line centered around it, and heavily fortifying Shanhai Pass to keep the enemy at bay. Worse still, consecutive famines and heavy taxes triggered widespread peasant uprisings that the court struggled to contain. In 1644, Li Zicheng’s rebel army captured Beijing; the Chongzhen Emperor committed suicide, ending the Ming Dynasty and establishing the Shun regime. The same year, guided by Ming general Wu Sangui, Qing forces entered Shanhai Pass, defeated Li Zicheng, and captured Beijing, marking the beginning of Qing rule over China.

Viewpoint 5:

Originates from the reduced strategic importance of the Western Regions.

Han and Tang valued the Western Regions because the Silk Road was thriving then, and the region was a vital trade artery.

But after the Mongol westward expansions, the overland Silk Road routes were severed. Combined with advancements in maritime technology, the strategic importance of the Western Regions greatly diminished.

Therefore, the Ming wasn’t focused on the Western Regions but prioritized Yunnan, the Northeast, and even Annam.

If it weren’t for the Dzungars (Zunghars) overreaching by trying to unify all Mongols, even the Qing might not have cared much about the Western Regions.

In the late Qing, with the frantic expansion of Tsarist Russia, the strategic importance of the Western Regions resurfaced, leading to Zuo Zongtang’s reconquest of Xinjiang.

Viewpoint 6:

With the Maritime Silk Road, the importance of the Western Regions was greatly reduced.

Clearly, maritime shipping was more convenient and faster. The main driving force for Han and Tang engagement with the Western Regions was the overland Silk Road – it had to bring economic benefits to interest the government.

The Mongols were inhumane, not only massacring the Western Regions’ population but also destroying water sources and polluting the environment.

An analogy would be locusts sweeping through…

Just established, the Ming faced widespread devastation in the Central Plains from the late Yuan wars, many areas depopulated. Rebuilding the homeland was the priority.

In essence, to Ming eyes, the Western Regions were likely a complete negative asset. Its status wasn’t indispensable, but maintaining its existence required constant transfusion of resources.

Viewpoint 7:

Gaochang, Khotan, Kucha, Yanqi… These Western Regions city-states, from Zhang Qian’s missions to Han Protectorates, to Tang direct rule, to Tibetan occupation, to the Guiyi Army/Uyghur Kingdom of Qocho period, to the Kara-Khanid Khanate period – the ruling class and even ethnicity might have changed generation after generation, but for a millennium, these city-state civilizations persisted So when did Xinjiang become the Xinjiang we are familiar with? Answer: After the Mongol Western Campaigns

Including Central Asia, historically synonymous with wealthy commercial cities – when did Central Asia become the impression of poverty everyone has?

Answer: After the Mongol Western Campaigns West Asia, land “flowing with milk and honey” with infrastructure dating back to the Akkadian Empire – when did it become desolate? How did Hetao, Guanzhong, and the Central Plains become wasteland? How did North Africa, the world’s granary, vanish?

Certain ideologies falsely accuse farming of destroying the environment. However, the settled nature of agriculture is precisely what protects the environment, maintains it, and creates ecological cycles. It’s the parasitic nomadic lifestyle, sucking a place dry then moving on to despoil another, that is characteristic of pastoral nomads. You’ll find that fertile lands across the Old World that endured for millennia or centuries were utterly destroyed only after being visited by various nomadic groups If not for two hundred years of Ming tree planting and land reclamation efforts, the North China Plain and Guanzhong Plain would have long since become desertified

How did the overland Silk Road vanish?

Answer: After the Mongols directly traversed (and destroyed) it.

Looking for a solid Bobe agent? agentsbobet seems pretty legit. Heard good things from my mates, thinking of giving them a shot. Anyone else tried them? You can find them here: agentsbobet

Kv999vips, VIP treatment, you say? Sign me up! Hoping for some sweet bonuses and maybe a lucky streak. Will report back! kv999vips