An Lushan died just one year after rebelling, so why did the An Shi Rebellion last for eight years?

Answer 1:

Because public opinion was controlled by the influential aristocratic families, they would not tell you that the deepest cause of the An Shi Rebellion lay in the rigid social stratification of the time. The Guanlong nobility monopolized the court, dominating exclusively, while scholars from humble and common backgrounds found their upward mobility blocked. Helpless, they had to go far away to the Hebei frontier, inciting An Lushan and Shi Siming to rebel, aiming to break the political stratification. An Lushan and Shi Siming and these common scholars used each other. Historians have long noted that figures like An Lushan and Shi Siming, whom the Tang court viewed as treacherous rebels, enjoyed deep popularity in the Hebei region. “It was customary to refer to Lushan and Siming as the Two Sages.” Thus, the so-called An Shi Rebellion was by no means accidental but was supported by a profound social foundation. The reason was simple: the Tang dynasty originated from the Guanlong nobility. Although during the reigns of Emperor Taizong and Empress Wu Zetian, the imperial examination system was implemented, vigorously supporting commoners, as an emerging political force, common scholars still lacked strength in the central government. The aristocratic families held absolute power in the central government. The rise of the imperial examinations provided new scholar-officials with opportunities to enter the court, but the examinations at that time were very corrupt. Many commoners had to spend years in Chang’an, as they needed to present their works to influential figures, much like Du Fu described: “Knocking on the doors of the rich in the morning, following the fat horses’ dust in the evening.” For those who still don’t understand, they can look at the real experiences of Li Bai and Wang Wei. Li Bai and Wang Wei were about the same age but had截然不同的境遇 due to their different family backgrounds. Nowadays, people’s understanding of Li Bai’s experiences is mostly imaginary, but the historical Li Bai had a very tough life. As the son of a merchant, he was not allowed to become an official. Li Bai spent his whole life wanting to be an official, to cleanse his family background, but was repeatedly disappointed. Due to poverty, he was looked down upon by a woman surnamed Liu with whom he lived, leading to divorce. His later years were even more miserable: he was exiled and had to rely on his wife, Lady Zong, living in destitution. On the other hand, Wang Wei came from the Hedong Wang clan, which originated from the Taiyuan Wang clan, one of the “Seven Eminent Clans and Five Great Surnames.” At fifteen, Wang Wei went to the capital to take the imperial examinations. Because of his talents in poetry, painting, and music, he quickly became a favorite among the nobility. (For those interested in these two figures, there is a link later for further reading.) Even so, the aristocratic families imposed many restrictions to suppress these emerging scholar-officials.

First, curbing the imperial examinations: Since they could not abolish the examinations, they controlled the selection process. Although the imperial examinations allowed scholars to become officials, one had to be recommended by local authorities to qualify for the exams. The aristocratic families controlled local and official circles, so unless one was exceptionally talented, most commoners were eliminated at the selection stage. Even if one was recommended and entered the examination hall to fill out the papers, they still could not compete with the aristocratic families. Unlike the later Song and Ming dynasties, where examinees’ identities were concealed ( papers were anonymized), during the Tang dynasty, examinees’ information was公开的 during grading. Examiners could check beforehand whether a candidate came from an aristocratic or common family, as well as their family conditions. If the civil service path was blocked, what about the military path? The Tang dynasty did not have a system of civil officials controlling military officials; military merit was also a path to advancement. If one found the civil service too difficult and thought of choosing the military path, they would fare even worse. For military advancement, one started as a勋官 (merit official), and different statuses led to vastly different prospects. In the process of becoming an official through military merit, children of officials had the advantage. After勋官 obtained散官 (honorary titles), civil散官 needed to be knowledgeable about current affairs to participate in selections. Official families could provide better educational opportunities and official connections, while ordinary people lacked such training and opportunities. Thus, fewer common people became officials through military merit compared to children of officials. Additionally, those who advanced directly through military achievements faced similar circumstances. Even for outstanding military exploits, appointments were divided into four grades based on family background, so children of nobles and officials naturally had an advantage over commoners.

Second, division and co-optation: Political marriages and maintaining retainers. Besides employing tough political tactics against commoners in official careers, aristocratic families also adopted strategies of division and co-optation. On one hand, they arranged marriages with newly successful examination candidates. Many commoners came from poor backgrounds. Once they leaped over the dragon gate ( achieved success), they were孤立无援. To advance further in their official careers, they had to attach themselves to great aristocratic families to seek higher political status. The best way for cooperation between the two sides was through marriage. Aristocratic families could拉拢 commoners for their own use and also打击 competitors. Famous “live-in sons-in-law” included Wei Gao, the military governor of Jiannan in the Tang dynasty. On the other hand, what about commoners who couldn’t become sons-in-law? It didn’t matter; even if they couldn’t become sons-in-law, being retainers was also quite good. The Tang dynasty emphasized master-disciple and幕僚 (advisor) relationships, like Zeng Tai and Di Renjie in “Detective Di Renjie.” Du Fu was once a retainer of the powerful Tang minister Fang Guan. To save Fang Guan, he ruined his own official career and wrote the famous “Du Fu’s Defense of Fang Guan.” The Old Book of Tang records: “Guan liked guests and enjoyed discussions. Using troops was never his strength, but the emperor, taken by his reputation, hoped for actual results.” Of course, only a minority of commoners were co-opted by aristocratic families. More commoners and lower-class scholars had no way to serve the country. For a time, places like Chang’an and Luoyang gathered many commoners like drifters. They either talked loudly in the city trying to attract the attention of these aristocratic families or died in despair away from home. During the Kaiyuan and Tianbao eras of Emperor Xuanzong, as the frontier regions expanded, these commoners with bleak prospects went to the Hexi and Hebei regions to seek opportunities. Many of these scholars filled lower-level local government posts or became advisors to frontier generals. For example, famous frontier poets like Gao Shi and Wang Changling often served as advisors to frontier generals in Hexi and Youzhou. For the aristocratic families controlling the central government, they were more than happy to see these commoners move farther away from Chang’an. Due to the Tang dynasty’s “Guanzhong本位思想” (Guanzhong-centric policy), these regions and frontiers lacked officials and intellectuals. The frontier regions were glad to accept them to strengthen their civil official teams. For instance, in Hebei, these commoners often studied纵横之术 (the art of diplomacy), discussing state affairs, and gained the trust of An Lushan and others. In An Lushan’s camp, people like Gao Shang and Zhang Tongru were from humble backgrounds. The most famous among them was Yan Zhuang. As a close advisor to An Lushan, Yan Zhuang was one of the key figures策划 the An Shi uprising. After An Lushan declared himself emperor, Yan Zhuang served as Zhongshu Shilang (Vice Director of the Chancellery). Later, he conspired with An Lushan’s son, An Qingxu, to murder An Lushan. After An Qingxu succeeded, he appointed Yan Zhuang as Yushi Dafu (Censor-in-chief) and Prince of Fengyi as a reward. “All matters, big and small, were decided by him,” so he wielded great power for a time. Later, seeing the decline of the An Shi forces, he surrendered to the Tang and became Sinong Qing (Minister of Agriculture).

Previously, many scholars pointed out that the An Shi rebel army had a distinct Hu (non-Han) character, often using Buddhism and Zoroastrianism to unite their followers and conduct political mobilization. However, this mobilization method often relied on specific religious beliefs, limiting its reach, especially for a religion like Zoroastrianism with strong Hu characteristics, which had limited influence in Han society. Therefore, it could only be used to unite the core forces of the rebel army. Even overemphasizing these foreign religious traits during the uprising could provoke Han scholars’ debates on夷夏正统 (the orthodox distinction between Han and non-Han). Thus, while using religions like Zoroastrianism and Buddhism to凝聚内部, the An Shi regime also had to find appropriate methods to win the support of Han officials and people who respected Confucianism as their cultural foundation, constructing a political ideology with both internal and external aspects. This was the role of Yan Zhuang and other common scholars. Since there is no biography of Yan Zhuang in the Old and New Book of Tang, we can only learn from the epitaph of Yan Zhuang’s father, Yan Fu, that using the traditional theory of the Five Elements’ cycle, with astronomical phenomena like the conjunction of five stars as omens of dynastic change, and promoting the theory of metal and earth replacing each other, was an important way for the An Shi regime to win hearts, win over scholars who emphasized Confucian orthodoxy, and construct concepts of legitimacy and political legitimacy for the dynasty. Even An Lushan’s choice of “Yan” as the name of his state was likely related to the prophecy mentioned in the epitaph: “The tail (constellation) corresponds to Yan; there must be a king beneath it.”

Thus, it can be seen that the An Shi Rebellion, in terms of class struggle, was more of a battle between the central aristocratic bureaucracy and scholars from lower-class families. Later, during the An Shi Rebellion, Luoyang and Guanzhong were successively occupied by the rebel army, and the Tang army suffered continuous defeats in the early stages. The Longyou aristocratic families were also severely damaged in this rebellion. On the other hand, the commoners were恰恰相反. They came from the bottom, were numerous, and rose rapidly during this great rebellion. They either served the An Shi regime or sought livelihoods in Hexi, Hedong, Jiannan, and Huainan. During the war, the commoners quickly rose, whether in the Tang camp or the rebel camp. Eventually, after the An Shi Rebellion, they formally entered the central government and competed with these Longyou aristocratic families. During the reign of Emperor Daizong of Tang, there were twelve chancellors. According to the “Tang Huiyao” (Institutional History of Tang), “There were twelve chancellors: Li Shi (Prince Yong), Miao Jinqing, Pei Zunqing, Yuan Zai, Li Fuguo, Liu Yan, Li Xian, Wang Jin, Du Hongjian, Pei Mian, Yang Wan, and Chang Gun.” Except for Li Shi, who later became Emperor Dezong of Tang, among the eleven, four were from aristocratic families, two were from humble common backgrounds, and six were jinshi (metropolitan graduates). This shows that starting from Emperor Daizong, the influence of aristocratic families gradually declined. Thus, the An Shi Rebellion was more like a struggle between the aristocratic forces around the emperor and the emerging commoner forces. The emerging commoner forces wanted to seize more political capital, while the decaying Guanlong nobility gradually declined in the game of the An Shi Rebellion. Moreover, with the decline of the Tang imperial power, the aristocratic families represented by the Guanlong nobility had to exit the historical stage.

In fact, that An Lushan died just one year after rebelling, yet the rebellion lasted for eight years, also shows that An Lushan himself, as a rebel, did not play as significant a role as some might think. What truly drove the rebellion were the vast number of scholars from humble backgrounds blocked from central power. Of course, after the An Shi Rebellion, the Guanlong aristocratic families declined, but the aristocratic families from east of the pass (Shandong) rose again. Later, the two sides gradually merged,同时利用科举打压底层寒门 (while using the imperial examinations to suppress the lower-class commoners), forming a new aristocratic monopoly on politics. This monopoly continued until the end of the Tang dynasty, finally disappearing under the slaughter of Huang Chao. Huang Chao himself was a failed examination candidate, also belonging to the common scholars. He delivered the final blow to the Tang aristocratic families, and the千年世家 (thousand-year-old families) collapsed. What truly resolved this contradiction was the rise of the imperial examination system in the Song, Ming, and Qing dynasties, providing commoners with a new path upward. However, due to the rigidity of the examinations later, new examination aristocratic families emerged, the so-called “righteous doors,” becoming new aristocratic families. This post is cited from Yutian Guanshihai, etc.

To avoid ambiguity, let me add: The frustration of commoners was the vanguard of the An Shi Rebellion, but behind it, there should be another black hand—the Shandong aristocratic families. Before the An Shi Rebellion, it was extremely rare for a commoner to become chancellor, except for those who climbed up during the great turmoil at the end of the Sui dynasty. By the time of Emperor Xuanzong of Tang, the Guanlong nobility truly occupied the court. In the early Tang, to consolidate the royal family’s position, Li Shimin practiced the “Guanzhong本位政策” (Guanzhong-centric policy), proposed by Chen Yinke. The original purpose of the Guanzhong-centric policy was to integrate the Hu and Han peoples in the Guanzhong region to对抗 (counter) the Northern Qi ( Bohai Gao family) and the Jiangzuo Xiao family. The New Book of Tang records: “The emperor (Li Shimin) spoke of people from Shandong and Guanzhong, implying differences.” Clearly, influenced by the Guanzhong-centric policy, Li Shimin still discriminated against the Shandong aristocratic families. Therefore, among the early Tang ministers, it was hard to find people from the “Five Surnames and Seven Clans.” The reason was that Li Shimin practiced the Guanzhong-centric policy,重用功勋之臣和天策府成员 (heavily relying on meritorious officials and members of the Heavenly策府). So, besides the factor of common scholars, the Shandong aristocratic families also pushed behind the scenes for the An Shi Rebellion. The Guanlong nobility not only suppressed commoners but also, together with the Tang royal family, restricted the Shandong aristocratic families. Compared to the Guanlong nobility occupying the central government, how could the Shandong aristocratic families not resent this? After the An Shi Rebellion, the “Guanzhong-centric policy” vanished, and the court’s recruitment system became more inclined towards the imperial examination system. The “Five Surnames and Seven Clans” families,凭借显赫的家学和优质的教育资源 (relying on their prestigious family learning and优质的教育资源), eventually returned to the peak through the imperial examination system. Before the An Shi Rebellion, few chancellors came from the “Five Surnames and Seven Clans,” but after the rebellion, the Xingyang Zheng family alone produced more than ten chancellors. The Qinghe Cui family produced only two chancellors before the An Shi Rebellion but eight successively after. The Zhaojun Li family produced seventeen chancellors, the Longxi Li family produced ten, the Boling Cui family produced fifteen, and the Fanyang Lu family produced over one hundred jinshi. Most of these occurred after the An Shi Rebellion. So, as I said later, after the An Shi Rebellion, the surviving Guanlong aristocratic families merged with the Shandong aristocratic families,继续利用科举打压寒门 (continuing to use the imperial examinations to suppress commoners). But compared to before the An Shi Rebellion, the upward mobility for common scholars increased somewhat. So, simply put, the Guanlong nobility was too greedy, monopolizing benefits, which angered everyone. Then, the Shandong aristocratic families, common scholars, and the底层胡人 (lower-class Hu people) joined forces to launch the rebellion. Eventually, the Shandong aristocratic families got the meat, the common scholars got the soup, and the Hu people were either killed or completely sinicized.

Answer 2:

After An Lushan died, the rebel army推出 (put forward) An Qingxu to continue resisting. After An Qingxu died, they推出 Shi Siming. After Shi Siming died, they推出 Shi Chaoyi. After Shi Chaoyi died, although the rebel army could no longer produce a leader to command the masses, they continued to resist under their respective leaders, forming藩镇割据 (regional warlord separatism). This makes it clear that the An Shi Rebellion was not just about An Lushan or Shi Siming personally. The hearts of the people in the region had changed. Even without An Lushan or Shi Siming, the rebellion would have happened; it was unavoidable.

Answer 3:

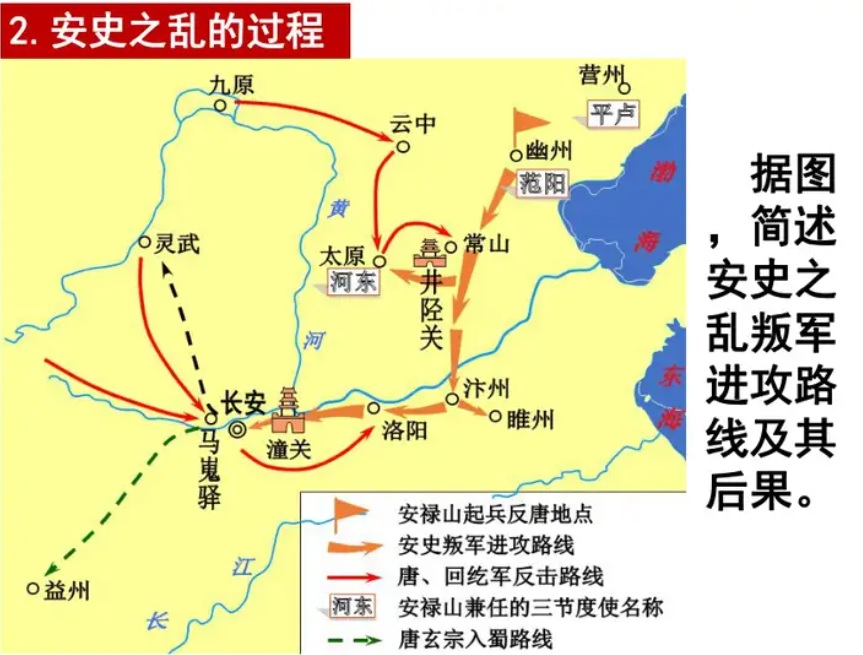

Because the rebel army was extremely capable of fighting. Over the eight years, in the decisive正面战场 (main battlefields), the Tang and the rebel army fought eight major decisive battles, with records as follows:

First battle, June 756: Battle of Lingbao, Geshu Han lost to Cui Qianyou. More than half of the Tang’s elites, the elite troops from Hexi and Longyou, were wiped out by Cui Qianyou without even seeing the main force of the rebel army. After this battle, Emperor Xuanzong fled, Consort Yang died, and Chang’an fell.

Second battle, October 756: Battle of Chentaoxie, Fang Guan lost to An Shouzhong.

Third battle, May 757: Battle of Qingqu, Guo Ziyi lost to An Shouzhong. An Shouzhong was a fierce general! Emperor Suzong had just ascended the throne; two major defeats left him dizzy. Especially the Battle of Qingqu—before this, the situation was actually favorable to the Tang army. An Lushan was killed, the rebel army had internal strife,部分主力叛逃 (part of the main force defected), and various generals were semi-independent. An Shouzhong’s army was isolated in the Chang’an area. Even in such a situation, the elite troops from Shuofang, Hexi, Longyou, Anxi, and Beiting, under the new commander Guo Ziyi, were severely defeated. The Tang’s finances and confidence were on the verge of collapse. Afterwards, they recklessly issued currency and hired回纥骑兵 (Uighur cavalry) at极其屈辱的代价 (extremely humiliating costs), all stemming from this.

Fourth battle, August 757: Battle of Xiangjisi (Incense Burner Temple), Guo Ziyi defeated An Shouzhong (A life-and-death battle for the Tang, staking everything. Many netizens in the comments mentioned this battle, calling it the peak confrontation of the冷兵器时代 (cold weapon era). Here are two additional details: At the time of出征 (setting out), Guo Ziyi swore to Emperor Suzong, “If this battle is not victorious, I will surely die!” At the most critical moment of the battle, the Tang’s last remaining force, the陌刀军 (long-sword army), which had returned from the万里西域 (distant Western Regions), stepped forward. Li Siye took off his armor, held a long sword, and shouted, “If we do not use our bodies as bait today, the army will be wiped out!”)

Fifth battle, October 757: Battle of Shanjun, Guo Ziyi defeated An Qingxu. The peak two battles of Guo Ziyi’s life. With the help of the Uighur troops (poor citizens of Luoyang), two major victories eliminated the main force of the rebel army and recovered the two capitals. According to the normal script, the An Shi Rebellion should have ended in the fourth year. However…

Sixth battle, February 759: Battle of Yecheng, the Tang army led by Guo Ziyi lost to Shi Siming. The联军 (allied army) of nine military governors—almost the entire family wealth of the Tang, supported by inflation, selling offices, and竭泽而渔 (draining the pond to get all the fish) financial means (all conceivable wealth accumulation methods were used at that time)— tens of thousands of Tang troops were惨败 (severely defeated) by Shi Siming at Yecheng in Hebei. Some historians even said, “After this battle, the Tang permanently lost Hebei.” Thereafter, although the An Shi Rebellion continued, Guo Ziyi could only leave黯然退场 (gloomily).

Seventh battle, February 761: Battle of Luoyang, Li Guangbi and仆固怀恩 (Pugu Huai’en) lost to Shi Siming. After the brilliantly fought Battle of Heyang the previous year, Li Guangbi continued his reputation as Shi Siming’s nemesis, stopping the rebel army’s development. But defense alone could not win the war; to eliminate the rebel army, a decisive battle was ultimately needed! However, at the foot of Beimang Mountain outside Luoyang, Li Guangbi lost all the chips he had previously won. (The upgraded Shi Siming 2.0 completed perfect revenge on the two mid-Tang talents. After Guo Ziyi, Li Guangbi also left the stage.)

I always thought that finding reasons to whitewash or shift blame for the defeat at Lingbao was understandable—just blame the emperor’s stupidity and Yang Guozhong’s misgovernment. For the defeat at Yecheng, shifting blame was barely acceptable—blame the emperor’s stupidity and Yu Chao’en’s misgovernment. But for the defeat at Luoyang, still finding reasons like this is somewhat不可思议 (unbelievable). Still the emperor’s stupidity? Pugu Huai’en’s misgovernment? Once or twice might be okay, but not three or four times. If history books are compiled like this, it can be considered a joke!

By this time, the Tang was山穷水尽油尽灯枯 (at the end of its rope). The Central Plains were completely occupied, Jiangnan was in ruins, famous generals had all fallen, elite troops were depleted, the court’s authority was扫地 (swept away), and soldiers from various regions were like bandits, looting everywhere (the consequence of inflation and reckless currency issuance). According to the normal script, the Tang should have perished. Finally, heaven showed mercy and favored the Tang—an extremely small probability event occurred: Shi Chaoyi killed Shi Siming. Two rebel leaders, two war-god-level famous generals, were both killed by their sons. Shi Chaoyi’s usurpation had more severe consequences than the previous two. The rebel leaders had followed Big Brother An Lushan to fight for the world. The first internal strife: Big Brother died, but supporting the crown prince wasn’t too big a problem—at most, it was being arrogant based on merit. Later, the second internal strife: the crown prince was干掉 (taken out) by Second Brother Shi Siming. Everyone could be on equal terms with Second Brother in a joint venture—after all, they were brothers (it still took Shi Siming a year to win over various leaders, missing the opportunity). But nephew Shi Chaoyi, who do you think you are? From then on, the rebel army分崩离析 (disintegrated). Tian Chengsi, Zhang Zhongzhi, Xue Song, and even Li Huaixian—none of them regarded Shi Chaoyi highly. At the moment when the Tang was on the verge of collapse, the rebel army collapsed first.

Eighth battle, October 762: Battle of Luoyang, Pugu Huai’en defeated Shi Chaoyi. Old rules: land归大唐 (returned to the Tang),子女玉帛归回纥 (children, jade, and silk went to the Uighurs). Rebel warlords in Hebei纷纷起义 (rose up one after another), receiving high positions and generous salaries. It呼应了 (echoed) that saying: Early revolution is not as good as late revolution, late revolution is not as good as counter-revolution! Large numbers of An Shi rebel main forces turned into the nightmare of the Tang for the next hundred years—藩镇 (regional warlords)!

Answer 4:

You are wrong; the An Shi Rebellion actually lasted far more than eight years. The reason the Tang stopped fighting was that they made peace with the rebel army, recognizing the rebel army’s complete power and status in the various provinces of Hebei. If they had not made peace, the An Shi Rebellion could have lasted until the fall of the Tang. Why did the Tang make peace? Because the Tang discovered that after so many years of fighting, the rebel army’s strength was still immense, while they themselves were about to collapse. The most important Jianghuai region of the Tang began to rebel. So, the Tang army made peace and immediately transferred troops to suppress the rebellion in Jiangnan. Later, the Tang fought many more battles with Hebei, resulting in continuous turmoil until the fall of the Tang. So, accurately speaking, the An Shi Rebellion lasted until the fall of the Tang. For most of the time in between, the Tang deceived itself, pretending this separatist force did not exist.一旦不老实,想削藩 (Once they acted up and wanted to reduce the power of the regional governors), the lower regions would immediately cause chaos, showing no respect.

Answer 5:

What you think rebellion is: An Lushan wanted to be emperor, so he rebelled.

The reality of rebellion: The world had long suffered under Chang’an; they pushed An Lushan to the front, saying, “Brother, let’s rebel.”

The so-called great prosperity of the Tang was built on the suffering of other places.

Answer 6:

It’s simple; there is nothing new under the sun, the standard answer for millennia…

Rural land兼并 (annexation) was too severe, the wealth gap was too large, and there were too many landless farmers in the countryside, leading to social instability. In such an environment, a single spark could start a prairie fire…

Then, you could see An Lushan, relying on the troops of three military governors, invincible throughout the world…

In all dynasties, the root cause of social turmoil lies in too many propertyless people at the bottom. Figures like Li Zicheng and An Lushan were merely troublemakers in such an environment. Without them, as long as this environment existed, there would be Ma Zicheng or哈士奇鹿山 (Husky Lushan)…

As for the lack of upward mobility for commoners, it was only a secondary reason…

Because without乱兵 (rebellious soldiers), even the most牛逼 (awesome) rebel general could be dealt with by a police station director…

Emperor Taizong of Tang’s famous saying: “Water can carry a boat; it can also overturn it.”

The water is the key…

Nowadays, why comprehensive poverty alleviation? It’s about caring for the feelings of the water…

Answer 7:

Because the questioner confused cause and effect. It was not because of rebellion that the Tang declined. Rather, because the Tang declined, social矛盾激化 (contradictions intensified) to a certain extent, leading to widespread rebellions. Comrade An Lushan was just one outstanding figure. Even if he died, the soil for uprising remained. In Chinese history, there were dozens of dynastic changes. When dynasties reached their end, there were peasant uprisings everywhere, and the world was in great chaos. These peasant uprisings eventually resulted in only one victor, who became the emperor of the new dynasty.

Answer 8:

Because the rebellion had little to do with An Lushan. The An Shi Rebellion was bottom-up; those people had accumulated enough resentment. Take the Battle of Xiangjisi as an example. The rebel army of 100,000 occupied Chang’an, facing the Tang army of 150,000. Both sides were elite armored soldiers. The rebel army attacked first, fighting from morning until evening. The process was boring: both sides hacked at each other. The first梯队 (echelon) was wiped out, then the second, then the third, until the main force was consumed. Then came the reserves, one team after another. Even if there were local surprise attacks, before they could be implemented, they were discovered by the enemy’s reconnaissance cavalry, turning the surprise into a frontal battle, then into monotonous and bloody mutual hacking. The final result: the Tang army lost 70,000, the rebel army lost 60,000, and 20,000 were captured. Finally, the remaining few thousand rebel soldiers could still retreat to Chang’an in formation without collapsing. You can imagine that rebellion was the true desire of these bottom-level people. It had little to do with the upper levels.

In ancient times, armies usually collapsed when casualty rates exceeded 10%. Here, both sides had casualty rates (killed and wounded) exceeding 60%, yet they fought to the death. The officers had no thought of preserving strength but sent their men wave after wave. And the soldiers were willing to die. These things required support from something within. Discipline alone cannot explain it.

To prevent being criticized about casualty rates and collapse, here is a quote:

“I have heard that those who were good at using troops in ancient times could make half of their soldiers die, the next best could make one-tenth die, and the next could make one-thirtieth die. Those who could make half die could impose their威加海内 (might on the world); those who could make one-tenth die could impose their力加诸侯 (power on the feudal lords); those who could make one-thirtieth die could make their orders obeyed by the soldiers.” From “Wei Liaozi”

CX777gamelogin seems useful. No issues getting signed in, and the process was smooth. Site felt secure, which is a big plus. If you’re looking for something reliable, try cx777gamelogin.

E aí, galera! Pinatawinsbr tá bombando! Tô curtindo demais os jogos e os bônus são show! Se você tá procurando um lugar novo pra se divertir, dá uma olhada lá. Vale a pena! Vai lá conferir pinatawinsbr!

long-term Beyond Memories delivers enduring memorial keepsakes, combining compassion and craftsmanship to create crystals and jewelry that honor loved ones and preserve cherished memories forever.

Best Garage Door Repair in Houston—fast, reliable, and affordable service you can trust. We fix broken springs, openers, cables, and doors with same-day repairs, expert technicians, and guaranteed customer satisfaction.